By Rick Synowski © 1995

** Originally published in the March/April 1995 issue of Arabian Visions magazine.

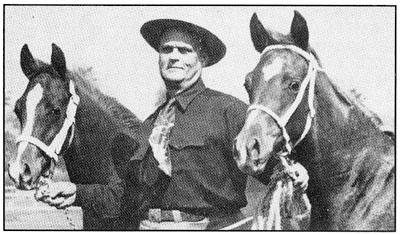

Like many kids looking for their first Arabian horse in the 1950's and early 1960's -- kids perhaps from less than affluent families and looking to make their dreams of owning an Arabian horse come true -- I first heard of Carleton Cummings after reading about his Skyline Trust Arabians. An article by H.H. Reese stated that Cummings had "developed his Arabian horse breeding program with the purpose of assisting boys and girls who like horses to secure good specimens of the breed on a partnership basis." Reese's article described Cummings' "lend lease" program whereby youngsters could lease a mare, breed her and then, after the birth of the foal, return either the mare or the foal. To an imaginative 11-year-old, this sounded like just the ticket. I wrote a letter to Cummings. Having read H.H. Reese's Kellogg Arabians a hundred times, I had pictured in my mind's eye the Arabian horse I wanted to own. I described this horse to Cummings in the first letter. Cummings replied with a post card. He stated he had about 2500 letters on his desk from youngsters across the country. If I was still interested, I was to write him again. I wrote Cummings that very day and so began a correspondence of some two years which culminated in buying half interest in a weanling colt, Skowronek's Antez, with my own savings in 1962. Cummings wrote the following spring that "few breeders ever get colts of this quality and even fewer ever offer them for sale." Nevertheless, he was giving me the opportunity to buy out his interest in the now yearling colt. I took Cummings up on his offer. It was a purchase I was never to regret. Within a few weeks Cummings died of a heart attack.

Cummings's background outside the sphere of Arabian horses was in music. He had been an operatic tenor of some notoriety in the east. He later turned to teaching as professor of music at Wake Forest College and later as the head of the music department at the University of Idaho. Cummings's wife, Theresa, had been a drama major in college where they met. After their marriage and graduation, they traveled to Army posts doing music and drama presentations during World War I.

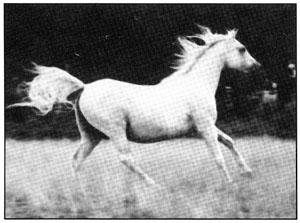

Cummings's background in music and theatre suited a personality that tended toward the theatrical, and a soul that was flamed by the same qualities in Arabian horses. His love for the dramatic carried over to the horses he purchased and bred and the ways he talked about them. However, his flowery descriptions were no means an exaggeration of the splendid group of horses he assembled.

His initial purchased in 1945 was the four-year-old Kellogg-bred Direyn (*Raseyn x Ferdirah). Cummings rode in a boxcar with Direyn the entire trip from Pomona, California to Moscow, Idaho. Cummings was to become part of "the Reese circle of breeders." Reese, having left the Kellogg Ranch as manager by then, and with a ranch of his own, continued in an influential role in the early Arabian horse community. Cummings's later purchases were from Reese himself, from that circle of cooperative breeders like the McKenna brothers, and from the Kellogg Ranch. Cummings's notable purchase outside this circle was Rifala's Lami (Geym x Maatiga, by Image) from Roger Selby in 1954. She was to become one of his most influential foundation mares.

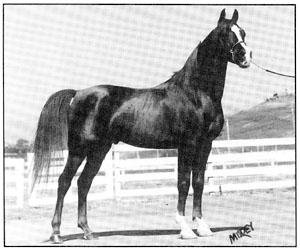

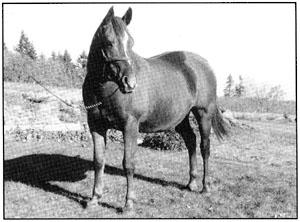

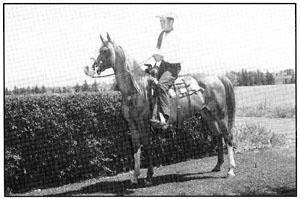

In 1949, Cummings purchased the weanling Abu Farwa son Antezeyn Skowronek (x Sharifa, by Antez out of Ferdith, by Ferseyn). He became Cummings's head sire. His progeny earned him a reputation as the third ranking son of Abu Farwa in the list of leading sires of show champions -- with many fewer foals on the ground than the first two ranking Abu Farwa sons. Antezeyn Skowronek ranked first of the Abu Farwa sons on another of Gladys Brown Edwards's lists: Abu Farwa sons whose own sons had sired show champions. Cummings himself claimed that for a three year period Antezeyn Skowronek had sired more ribbon winners than any sire of any breed. This was entirely possible since his progeny were in the hands of an army of horse-crazy, show-happy kids who would take their Skyline charges to every local show, weekend after weekend, entering dozens of classes in every division from halter to three-gaited to gymkhana events -- and winning. These Antezeyn Skowronek offspring were notable not just for their quality and sheer beauty. And their successes were not limited to the competition of local shows. In 1958, the Pauley girls took their young Antezeyn Skowronek daughter, Khatum Tamarette, on the road, first to Estes Park, Colorado, to take 1959 U.S. Top Ten Mare; then to Yakima, Washington, to win Pacific Northwest Champion mare; and finally to Calgary to win a Top Ten at halter. These victories, which Cummings later described as no small feat of endurance for a young mare, earned her the Legion of Merit, one of the first mares to earn this award.

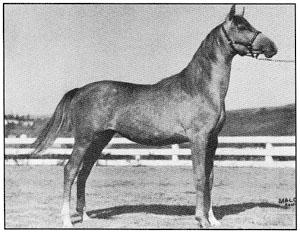

Cummings's band of foundation mares numbered at 16. He selected these mares to complement Antezeyn Skowronek, but each was chosen on her own merits. Four of his mares were daughters of Ferseyn, taking Reese's lead to cross Ferseyn daughters with Abu Farwa, and Abu Farwa daughters with Ferseyn, an idea which echoed Lady Wentworth's earlier cross of Skowronek and Blunt lines. Cummings purchased the Farnasa daughter Anazeh's Nijm from the Kellogg Ranch, in partnership with one of his protegees, Mary Hall. Anazeh's Nijm was bred to Ferseyn prior to shipping her home. The resulting foal was the chestnut colt Ferseyn's Rasim, whom Cummings traded Mary for full interest for his interest in the mare. Ferseyn's Rasim became Cummings's junior sire and proved himself an excellent cross on Antezeyn Skowronek daughters as well as on Skyline foundation mares. Two of Cummings's foundation mars were daughters of the Antez son Gezan, a popular southern California sire of the early 1950's. Antezeyn Skowronek himself was a grandson of Antez, a Kellogg sire of 100% Davenport breeding who ended an international career as a successful sire himself at the Reese ranch. The Davenport influence was an important presence in the Cummings breeding program.

Cummings was a somewhat controversial figure and outside his band of young, loyal protegees, he was not always well liked. He did not seem to care, and used to say "It doesn't matter what people say as long as they keep talking about you." This advice must have harkened back to the days when he performed on stage. Cummings was outspoken and did not mind stating his opinions while sitting in the stands at a horse show. If sitting on the same side of the arena as Cummings, everyone got to hear his opinions, which sometimes referred to the horses in the ring, whether they wanted to hear them or not. It was a little embarrassing for the youngster such as I who was sitting at his side. Cummings also made enemies of a few breeders who had horses for sale at fancy prices. Cummings's kids sometimes beat these breeders in the show ring with horses leased from Cummings or sold by Cummings at bargain basement prices. And the parents of competing kids must have been sitting in the stands bored stiff watching the Skyline horses entering, and often winning, class after class.

Cummings was not in the habit of getting things down on paper and sometimes made agreements or promises he did not remember. After his death, his daughter inherited his estate, which included the horses. I told her Cummings had promised Wafa El Shammar to me to breed to my colt. His daughter told me six other people had written to tell her Cummings had promised this mare to them. (I did get Wafa El Shammar, who became my foundation mare.)

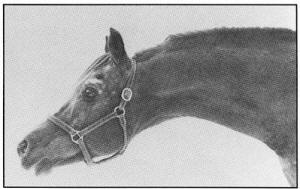

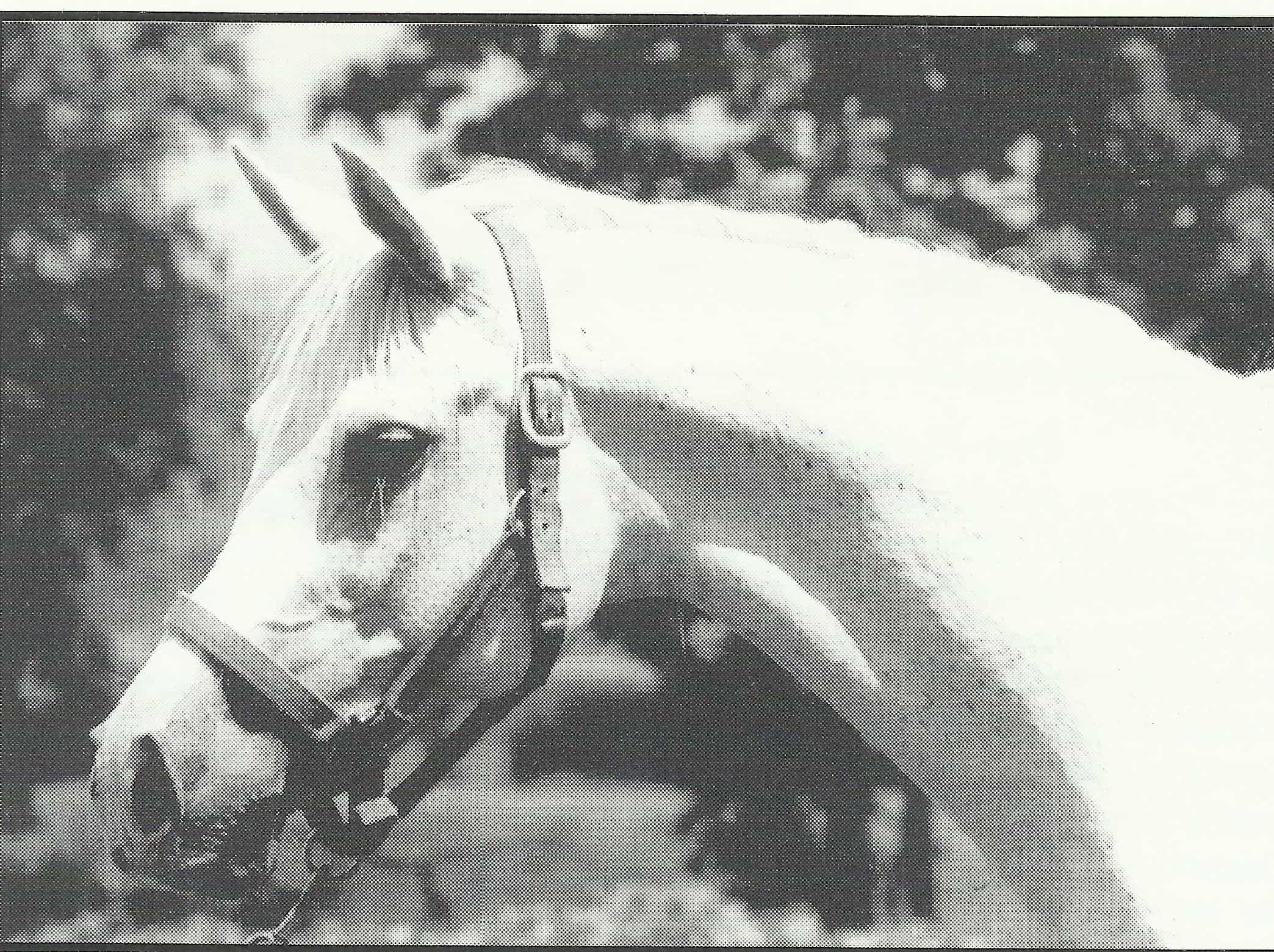

Despite these discrepancies, Cummings was a real horseman and a genius as a breeder. The horses he selected and bred from were outstanding for their "tangible as well as intangible qualities." Most of his horses were mounts and companions for youngsters. Few of the horses were ever trained or shown by professionals, but were remarkably successful nevertheless. As breeding horses, they were notable for their ability to consistently produce first rate stock. Cummings's advertising slogan "Home of beautiful heads and great performance horses" was an accurate description of the Skyline Arabians, as was another of his slogans, "bred for and born with spectacular action." Cummings admired the Crabbet-bred Naseem for his exceptional beauty above all other ancestor horses, and the Crabbet-bred *Berk for his spectacular action. He used to brag about the number of crosses his horses had to those icons of Arabian horse breeding. Cummings also admired *Raffles. He used to say he liked a "touch of *Raffles for beauty" in his horses. His statement no doubt reflected his delight with the foals of Rifala's Lami, especially the Antezeyn Skowronek son Rifala's Naseem. Cummings described Rifala's Naseem as a "peacock of horses" and "well worth traveling 10,000 miles to see him." From his pedigrees-in-a-name (another of Cummings's idiosyncrasies) his pride in these particular ancestors of Rifala's Naseem is obvious.

Perhaps most important of all, Cummings provided an opportunity for kids to have their dreams come true - not just to own an Arabian horse, but to own a good one. Cummings stressed hard work and responsibility to these youngsters, but his most often heard advice was "to dream big."

Last Updated: April 22nd, 2019

Comments

No Comments